Retinal Vascular Occlusion

What are Retinal Vascular Occlusions (RVOs)?

A retinal vascular occlusion is a blockage of the retinal vessels, either the arteries or the veins, in the back of the eye. If these blockages took place in the brain they would be called a stroke. As a result, we often call these problems “a stroke in the eye.”These blockages have different causes usually relating to a systemic disease and in order to understand the problem it is necessary to have some understanding of eye anatomy.

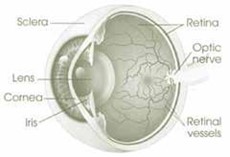

The eye is a spherical structure with the lens of the eye that focuses light in the front. In the back of the eye is the retina, which converts the images on the retina into electrical impulses and sends them along the optic nerve to the brain. The retina has both arteries and veins. In most patients, there is a single artery or vein that enters the eye through the optic nerve. These are called the central retinal artery and the central retinal vein.

In the retina, the arteries and veins spread out to the periphery of the retina and the arteries and veins cross each other. These crossing points can cause problems as you get older because if the arteries become thickened, they can compress the vein. More about this later in the section on branch retinal vein occlusions.

What are Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) and Hemi-Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (HCRVO)?

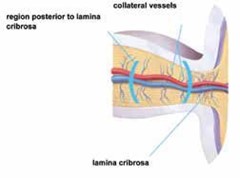

A blockage of the main vein in the eye is called a central retinal vein occlusion. The blockage of the vein takes place in the optic nerve behind the retina. Because the blockage takes place outside the eye in the optic nerve, it usually affects the entire eye and vision may be severely affected. In some patients there are two or more central retinal veins. These patients can have occlusion of only one of these veins and have what is called a hemi-central vein occlusion. These often cause less damage than a full central vein occlusion.

Most patients who have this problem have risk factors for vascular disease.This may be diabetes, high blood pressure, arteriosclerosis, open angle glaucoma or a condition called thrombophilia. In younger patients, usually under age 40, we check for clotting disorders. We may find an important abnormality that needs to be treated. If there is a family history of strokes or miscarriages or if the patient has autoimmune problems, then the tests are particularly important. Since these problems are stroke-type events, we request that you check with your primary care doctor for a review of your medical condition.

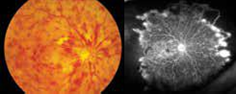

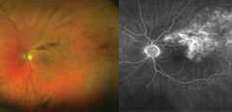

The blockage causes blood to back up in the eye, which causes hemorrhages, swollen retinal veins, and edema or swelling. This often leads to visual loss. If the occlusion is severe, there can also be marked ischemia or closure of the capillaries. This can lead to abnormal vessels in the eye (neovascularization), hemorrhage into the vitreous, and even abnormal vessels in the front of the eye that can lead to high pressures and glaucoma (rubeosis).

Central retinal vein occlusion: Photograph and fluorescein angiogram Note accumulation of dye in the center of the retina (leakage), and the loss of blood vessels in the peripheral retina.

It has been noted for forty years that some central vein occlusions are severe leading to blindness and complications and others are less severe with some visual loss but maintenance of some vision. Those eyes with severe vein occlusion have blood vessel closure (ischemia) and are more likely to have problems.

What is a Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO)?

Schematic of branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) with compression and blockage of the vein (blue) by a thickened, stiff artery (red).

Most patients who have this problem have risk factors for vascular disease. This may be diabetes, high blood pressure, arteriosclerosis, open angle glaucoma or a condition called thrombophilia. In younger patients, usually under age 40, we check for clotting disorders to see if there is a clotting problem. The yield is not great, but sometimes we find an important abnormality that needs to be treated. If there is a family history of strokes or miscarriages or if the patient has autoimmne problems, them the tests are particularly indicated. Since these problems are stroke-type events, we request that you check with your primary care doctor for a review of your medical condition.

These blockages may not have any symptoms if the occlusion does not involve the macula. If the macula is involved, then there can be swelling of the retinal tissue that can lead to visual loss (macular edema).

The most common systemic cause for BRVO is hypertension. It can also be seen in arteriosclerosis and diabetes. Sometimes there is no associated problem.

How do Retinal Vein Occlusions cause loss of vision?

Macular Edema

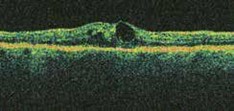

The major cause of vision loss in retinal vein occlusion is macular edema. The macula is the central retina and is responsible for fine detail vision for reading, recognizing faces, and driving. The macula is an intricate and delicate structure that needs to have proper connections and needs to be free of swelling with fluid (edema). In retinal vein occlusion, the blockage of the veins results in leakage of fluid and blood through the blood vessel walls. This is much like what happens when a garden hose is plugged and water leaks through the wall of the hose due to the increased pressure and/or damage to the rubber wall.

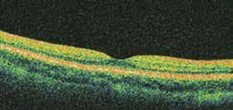

We are able to diagnose and monitor this complication with a test called Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) scan. The OCT scan provides a cross section of the macula to evaluate its thickness and structure. In a normal OCT scan, the central macula has a thickness of between 150 and 250 microns (one fourth of a millimeter). A central depression called the foveal pit is what gives one the fine-detailed 20/20 vision.

In macular edema, fluid accumulates and causes the macula to swell like a sponge. As a result, vision can be distorted or blurred, and the images may be magnified or minified, much as when looking through a glass of water.

What treatments are available for Retinal Vein Occlusions (RVO)?

Anti-Angiogenic Drug Injection

For patients with macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusions, anti-angiogenic intravitreal injection is usually the therapy of choice. The FDA has approved Lucentis, Eylea and Vabysmo, which are Vascular

Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) inhibitors, for injection into the eye. A fourth VEGF inhibitor, Avastin, has been approved by the FDA for injection into veins as a cancer therapy, and is used as an “off-label” therapy for retinal vein occlusion as well. However, it is formulated in a compounding pharmacy, which may have additional risks as compared to medications prepared specifically for eye injections by pharmaceutical companies. A relatively painless technique to inject a small amount of the VEGF inhibitor into the vitreous cavity of the eye has been developed.

Treatment with Lucentis

Lucentis is an antibody against the molecule that causes macular edema and the growth of abnormal vessels (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor or VEGF). It is effective in improving vision and clearing macular edema in retinal vein occlusion. Vision improvement is rapid and seen, on average, by seven days. Patients are typically started on monthly injections and once the edema is resolved, slowly extended on longer intervals between injections. The ongoing need to for treatment varies among patients from months to years.

In CRVO, 48% got significantly better (3 lines or better on the visual acuity chart) compared to 17% in the control group (observation).

In BRVO, 61% improved by at least three lines compared to 29% in the control group (observation + macular laser).

Treatment with Eylea

Eylea is another VEGF inhibitor ap- proved for treatment of retinal vein occlusions in 2014.

In CRVO 56% of patients had significant vision improvement (3 lines or better on visual acuity chart) compared to 12% in the observation group.

In BRVO 53% of patients had significant vision improvement (3 lines or better on visual acuity chart) compared to 27% in the (observation group + macular laser group).

Treatment with Vabysmo

Vabysmo (faricimab, Genentech) is a more recent medication FDA approved for the treatment of retinal vein occlusion. Vabysmo is an antibody that acts against both VEGF and Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2). Some patients may require less frequent injections with Vabysmo while maintaining the same visual gains noted with Lucentis and Eylea. Retina Associates of Florida was involved in this clinical trial and is proud to have been able to provide this cutting edge treatment earlier to patients.

Treatment with Avastin

There is another anti-VEGF drug called Avastin. This drug is FDA approved for the treatment of cancers and has also been shown to work for macular edema. We prefer to use Lucentis, Eylea or Vabysmo when possible because they have been shown to work in large clinical trials, and it is prepared under

Future Treatments on the Horizon for Retinal Vein Occlusion

Retina Associates of Florida participated in a clinical trial looking at the use of KSI- 301 (Kodiak Sciences) in patients with BRVO and CRVO. KSI-301 is also an eye injection of an anti-VEGF medication that is built on an Antibody Biopolymer Conjugate which is thought to allow a longer duration of therapy. Patients were able to maintain the same visual benefits with fewer injections and we expect this medication to become FDA approved and available commercially for our patients in the near future.

Treatment with Steroids

Another option of treatment is using intraocular steroid medications. The SCORE trial was a large, multicenter trial that demonstrated a benefit in CRVO but not in BRVO. However, there is a significantly higher risk of glaucoma and cataracts in patients given steroid injections, especially if they need to be repeated.

There is also a long-acting steroid implant called Ozurdex, which contains a different steroid, dexamethasone. There is also significant risk of cataract and glaucoma and the duration does not appear to be significantly different than triamcinolone. While we believe that anti-VEGF injections are a better, safer choice for most cases, sometimes steroid treatment by itself or in combination with anti-VEGF therapy may be warranted.

Treatment with Laser

In two large, multicenter clinical trial conducted in the 1990’s (the Central Vein Occlusion Study, or CVOS), and the Collaborative Branch Vein Occlusion Study, or BVOS) demonstrated that laser treatment to the macula (the center of vision) demonstrated a benefit in BRVO but not in CRVO. Since the advent of anti-VEGF injections which are significantly more effective at improving vision, we rarely ever use macular laser treatment.

However, laser treatment outside the macula (peripheral or scatter laser) was demonstrated to be effective when abnormal blood vessels grow in the retina or iris (neovascularization). This is a rare but serious complication that can result in bleeding inside the eye (vitreoushemorrhage) and increased eye pressure (neo-vascular glaucoma).

What are retinal artery occlusions?

The arterial circulation of the eye can become occluded just like the venous system. What you see inside the eye is completely different. In a vein occlusion there is edema and hemorrhage. In retinal artery occlusion, the retina turns white.

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Patients with central retinal artery occlusion lose vision suddenly. Unfortunately, the visual loss in central retinal artery occlusion is usually irreversible although there may be some improvement over time..

There is no good treatment of central retinal artery occlusion. Lowering the eye pressure or breathing into a bag have been advocated, but they don’t seem to help.

Treating the artery occlusion aggressively like you would a stroke in the brain with TPA (tissue plasminogen activator) has also been tried, but without success.

If you have a central retinal artery occlusion, it is important to figure out why. Retinal artery occlusions are considered stroke events and urgent medical evaluation for stroke should be carried out in a hospital emergency department.

Sometimes these problems are caused by emboli from the heart or the carotid artery. Sometimes the blockage is a thrombus that forms in the artery itself with an aggregation of platelets (like the Plavix commercials on TV). Patients with an artery occlusion need to be checked by their doctor and usually have a carotid ultrasound to rule out disease there and an echocardiogram to rule out a clot in the heart. In younger patients there may be a heart condition called patent foramen ovale where there is a hole between the right heart and the left heart and emboli can cross into the arterial circulation. Patients also need to control their cholesterol and high blood pressure if elevated. Usually, such patients are treated with anticoagulants such as aspirin or Plavix.

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion:

Like in vein occlusions, sometimes only a part of the retina is involved and this is a branch artery occlusion. The same risk factors related to central artery occlusions also apply to branch artery occlusions. Emergency medical evaluation should be undertaken.

There is a unique subset of retinal emboli where the ophthalmologist can actually see flecks of cholesterol in the eye. Sometimes they block the artery and sometimes not. Patients with the plaques in the retina called Hollenhorst plaques after the doctor who first reported them, need to be evaluated to rule out carotid artery disease and hypercholesterolemia.

What is Ischemic Optic Neuropathy?

Another vascular disease that affects the eye is an occlusion of the choroidal vessels around the optic nerve. This can lead to sudden visual loss and usually affects the upper or lower field of vision. There are no currently proven treatments although steroids and anti-VEGF drugs like Lucentis have been tried.

Ischemic optic neuropathy may be caused by hypertension or arteriosclerosis. It is also associated with temporal arteritis, an inflammatory disease of the arteries of the head. Additional symptoms with temporal arteritis are headaches, difficulty chewing, feeling tired, difficulty getting hands above the head, scalp tenderness, and weight loss. Patients suspected of this condition need blood work, a sed rate and c-reactive protein. Often a biopsy of their temporal artery is needed to confirm the diagnosis. The treatment for temporal arteritis is high dose steroids so it is important to be sure of the diagnosis if treatment is going to be continued for a long time.

Ischemic optic neuritis has also been associated with drugs to treat erectile dysfunction like Viagra. If you are taking these drugs, it is important to stop and be evaluated.