Nevus and Melanoma of the Eye

What is a nevus?

A nevus is a patch of pigmented cells in the uveal layer of the eye. It is usually benign and is often described as a freckle of the back of the eye.

What is the uvea?

The uvea is the middle layer of the eye. It is the layer in the back of the eye between the retina and the tough outer layer of the eye called the sclera. You may think of it as the meat part of a sandwich. In the front of the eye, the uveal layer is the iris which is the brown pigmented or blue part you see in the front of your eye.

What is a suspicious nevus?

A suspicious nevus is usually a nevus that is larger than the more common benign nevus, or is elevated/not flat. There are several other characteristics in the front part of your eye that may indicate that a nevus has a higher risk of becoming or being a melanoma.

How is a suspicious nevus managed?

Photographic and ultrasound measurements are made initially and at regular intervals thereafter. If the lateral borders or thickness of the suspicious nevus increase significantly, malignant transformation to a uveal melanoma is assumed to have occurred. There are other changes, such as subretinal fluid or orange pigment on the surface of the nevus that support this conclusion.

What is a uveal melanoma?

A uveal melanoma is a tumor of the uveal layer of the eye, either in the iris or in the posteriorly located uvea called the choroid. Tumors in the back of the eye under the retina are usually referred to as choroidal melanomas.

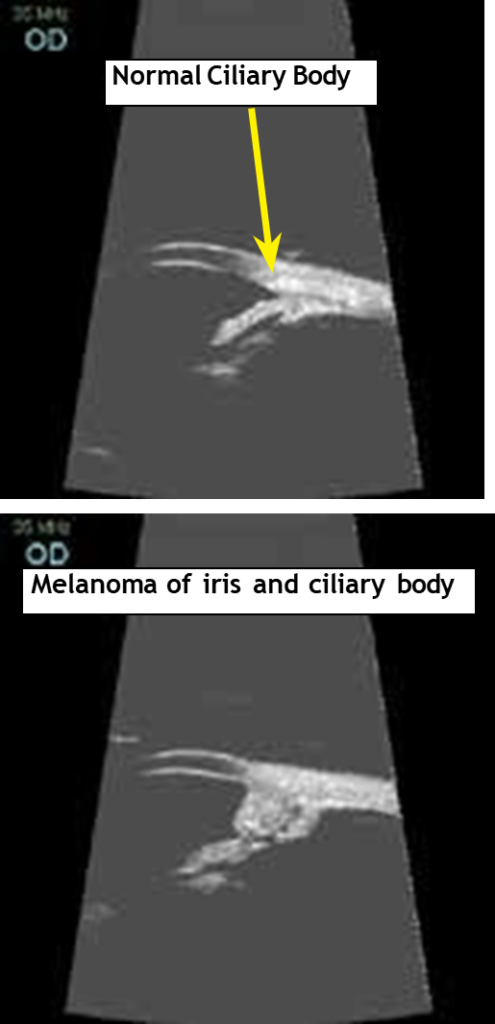

The part of the uvea between the retina and the iris is called the ciliary body. Ciliary body melanomas are harder to see because they are often hidden behind the iris.

How is choroidal melanoma diagnosed?

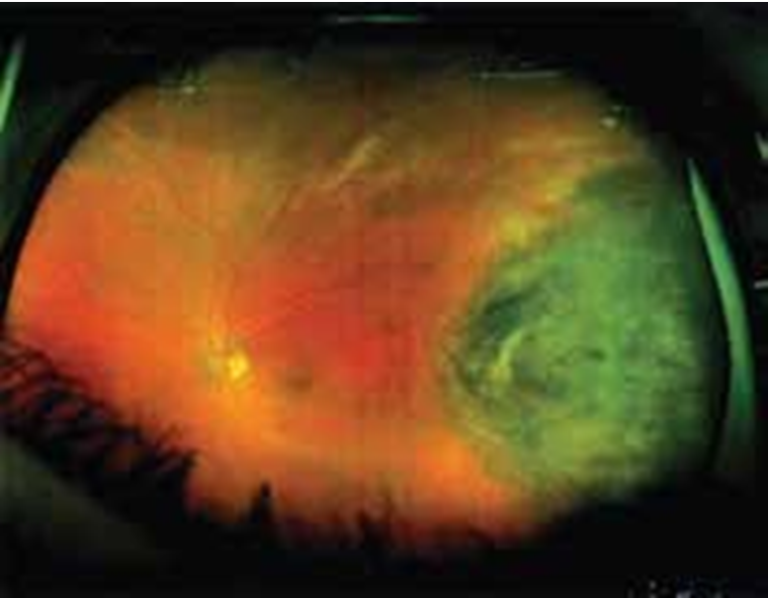

Melanomas that develop from suspicious nevi are diagnosed by following the suspicious nevus for interval growth or the development of other risk factors. More commonly, a choroidal or ciliary body melanoma is found on its initial observation. The appearance of the tumor seen by the retinal specialist with the indirect ophthalmoscope is often diagnostic.

Positive risk factors for melanoma are elevated lesion, subretinal fluid, orange pigment or other pigmentary irregularity, and absence of drusen. Sometimes the only initial sign of a ciliary body melanoma is the appearance of enlarged blood vessels on the outside of the eye.

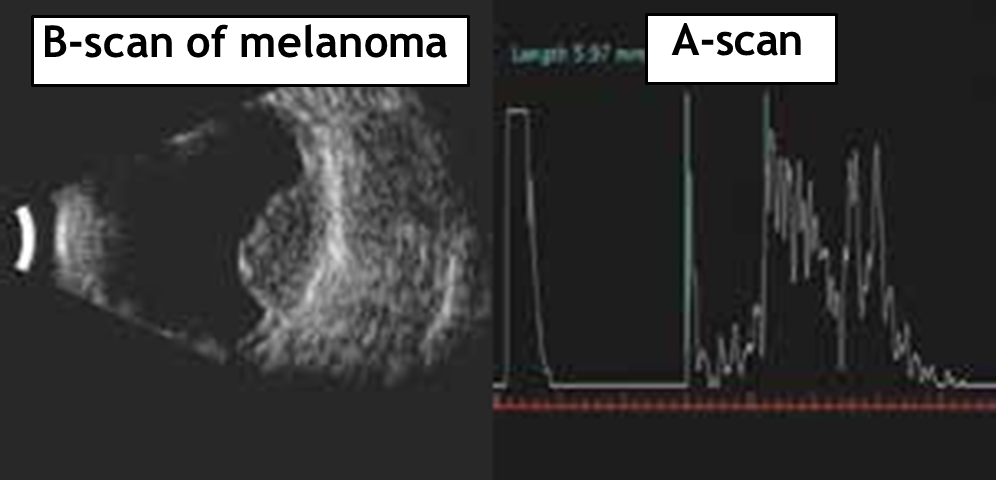

Because accurate diagnosis is so important, additional tests are done to confirm the diagnosis. The A-scan and B-scan ultrasound tests measure the dimensions and the ultrasonic reflective structure of the melanoma. A fluorescein angiogram is usually done to confirm tumor circulation and rule out hemorrhagic choroidal detachment.

A special ultrasound called the Ultrasonic Biomicroscope is used to evaluate the ciliary body and iris melanomas.

Tissue biopsy can be performed with a fine needle in cases where the diagnosis is still uncertain. However, fine needle biopsy is seldom required to reach a high enough level of certainty to prescribe treatment of the uveal melanoma.

How is it treated?

Once the uveal melanoma has been diagnosed, the next step is to make sure the melanoma has not spread to the liver or other parts of the body. Tests such as liver function blood tests, chest x-ray, ultrasound of the liver, and PET-CT scan are often ordered for this purpose. If the uveal melanoma has spread to other parts of the body, the patient is usually referred to an oncologist (cancer specialist) for further evaluation and treatment.

If there is no specific finding of the uveal melanoma spreading to the rest of the body, the objective is to prevent the tumor from spreading. Due to the life-threatening nature of tumor spread, the main goal of treatment is preservation of life. Saving the eye and saving the vision are second and third priorities

Most tumors are small to medium size (under 9.0 mm in height). Thesetumors can be treated with a radioactive iodine-125 plaque here in Tampa. The plaques are inserted in a hospital surgical setting. Most patients are discharged home the same day with the plaque in place. The plaque must be removed, which is usually done about a week later.

For tumors larger than 10mm, the plaque is not adequate to treat the melanoma. The eye can be removed (enucleated) here in Tampa or, in many cases, treated with proton beam approach available in Jacksonville, Boston, and California. The proton beam is also used to treat uveal melanomas which are large and located in the ciliary body. The retinal surgeons at RAF in Tampa will surgically implant clips on the sclera overlying the melanoma prior to referral to the Jacksonville Proton Therapy Institute. These clips allow the proton beam to be aimed accurately at the melanoma.

Surgical resection of iris melanomas is occasionally performed if the tumor is expected to be low grade and small. Surgical resection of other uveal melanomas is not widely practiced and would only be done after radiation treatment to minimize the risk of spreading the tumor outside of the eye.

A fine needle-aspiration biopsy (FNAB) at the time-of or before radiation treatment is often offered to the patient to determine the melanoma cell genetic type. The FNAB results show the probability of the melanoma spreading to the rest of the body in the next few years. Although there is no proven preventive treatment for high risk FNAB results at this time, there is much research activity in this area. Complications of hemorrhage and retinal detachment from FNAB may result in further visual loss.

How is it followed?

The eye will be checked at regular intervals after completion of radiation treatment. Generally, ultrasonography and photography of the melanoma are used to measure regression. The first post-radiation treatment measurement of the melanoma isn’t usually performed until 6 months because the tumor regression is often slow, and the tumor may swell slightly in the first few months after radiation treatment.

Systemic monitoring for tumor spread to the rest of the body is performed by an oncologist every 4-12 months depending on results from the FNA biopsy. The testing usually consists of a combination of blood tests, chest x- ray, ultrasound of the liver, MRI of the abdomen or PET-CT scan. Radiation retinopathy and optic neuropathy are a frequent complication beginning the first year or two after tu-mor treatment near the macula or optic nerve. If vision is lost or threatened, laser and/or injections of anti-vascular- endothelial-growth-factor (anti-VEGF) may help. Proton beam treatment can also cause loss of eyelashes as well as radiation scarring of the lids and conjunctiva.

What other tumors are seen in the back of the eye?

Primary tumors of the breast, gut, and prostate (as well as others) may be detected first as a metastasis to the uvea. This also can occur with recurrent previously treated tumors outside the eye. Usually, the uveal metastasis will be controlled by systemic therapy for the primary tumor. External-beam x-ray therapy of the eye can be used if systemic therapy is ineffective or can’t be used.

Hemangiomas of the uvea and retina are not malignant tumors. They are tumors of the blood vessels. In these, the objective is preservation of as much vision as possible. Several non- radiation therapies such as anti-VEGF injection, laser photocoagulation, photodynamic cold laser, cryopexy, and surgical excision can be used. Radiation therapy can also be used in difficult cases.